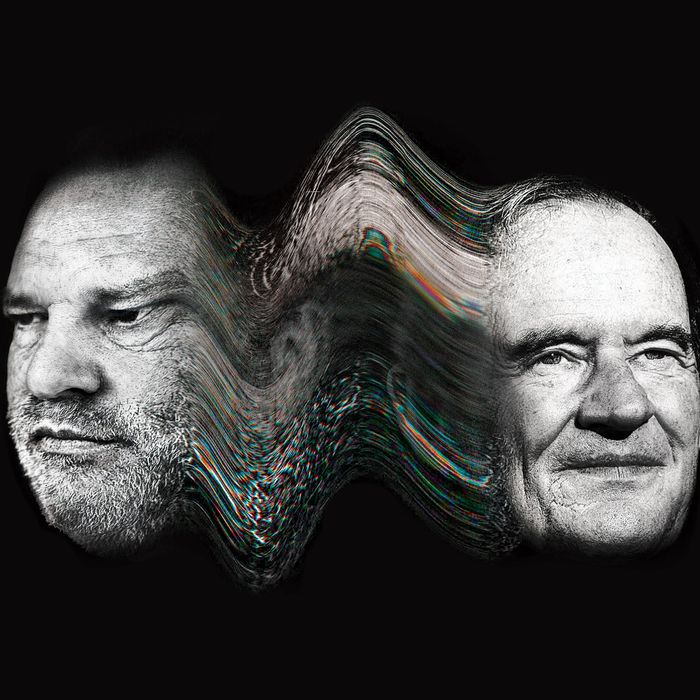

One day in November 2000, David Boies was in his backyard in Westchester planting a copper-beech tree with the help of a client, a billionaire real-estate developer, when he received an unexpected phone call. It was someone from Al Gore’s campaign begging him to take on the most important case in America. Gore was trying to overturn his 537-vote loss in Florida and, with it, George W. Bush’s lead in the Electoral College. Boies, a Democrat who was one of the country’s most skilled — and feared — courtroom litigators, ended up arguing Bush v. Gore all the way to the Supreme Court, losing valiantly in a decision with many fateful ramifications. For Boies, one was an introduction to a man who would become one of his most devoted clients, the movie producer Harvey Weinstein.

Within the legal profession, Boies was already a legendary figure. But Bush v. Gore gave him a taste of national celebrity. Bill Cosby cold-called to introduce his agent, who pitched him on writing a memoir. Tina Brown, who was then running the magazine Talk, pursued him as a potential author for a new, Talk-related publishing imprint. She invited Boies to lunch with her financial backers, Weinstein and his brother, Bob.

They offered Boies a substantial advance for his memoir, and before long, Boies was also acting as their legal counsel. “That’s how Harvey pursued things,” says an attorney who worked for Weinstein. “Give him a book deal and then he’d have a relationship with the greatest fucking lawyer there is.” With others, Weinstein may have acted like a crass bully, but he treated Boies with great deference, calling on him for matters large and small.

When the Weinstein brothers wanted to extricate themselves from an unhappy marriage with Disney, Boies acted as their divorce attorney, threatening a $400 million lawsuit. (It worked.) When Michael Moore was fighting with the Bush administration over a reporting trip to Cuba for the documentary Sicko, Boies and Weinstein staged a bellicose press conference with the filmmaker, resulting in a bunch of beneficial headlines.

Sometimes, though, Weinstein wanted problems to disappear quietly. As early as 2002, Boies was aware that Weinstein had paid legal settlements to women who’d accused him of sexual misconduct. That year, he represented Weinstein in meetings with The New Yorker writer Ken Auletta, where Weinstein lobbied the journalist not to report the settlements in a profile.

Weinstein employed many attorneys, but Boies was the one he would bring up whenever he was in serious trouble. One person who tangled with him recalls, “Harvey, over the years, would often threaten, ‘If you don’t do this, you’re going to hear from David Boies.’ ” His name was often wielded like a weapon by the demanding men he represented (others in the fraternity included George Steinbrenner, Hank Greenberg, Larry Ellison).

Today, Boies’s name has taken on a different meaning. Where once he was heralded as a liberal lion — a champion of marriage equality, a defender of press freedom — now he has been recast as the general counsel for the patriarchy. Boies was at Weinstein’s side last year, still whispering in his ear, when decades of grotesque allegations, ranging from harassment to rape, finally burst through their protective defenses. Boies now stands accused, at least in the court of public opinion, of participating in a yearslong effort to silence women and shield an alleged serial sexual predator.

His protests of ignorance — Boies recently pronounced himself “shocked” by the Pulitzer-winning New York Times and New Yorker stories that revealed the extent of the allegations against Weinstein — have been belied by the extreme tactics employed to keep those articles from being published. Most controversially, Boies’s law firm contracted with a private-investigation outfit called Black Cube to stage an undercover surveillance operation targeting journalists and alleged Weinstein victims.

“I think Boies’s behavior was part of a culture of complicity,” says Deborah Rhode, a prominent scholar of legal ethics at Stanford University. “If he had no knowledge, it’s because he and people like him helped to suppress that information.”

For Boies, at 77, the consequences have been reputation-shattering. The revelations of the past year have opened everything about his life and career to reassessment, from the ethos of his firm, which pops up with eerie regularity in notorious scandals — it represents Oleg Deripaska, Paul Manafort’s oligarch business partner; Elliott Broidy, Donald Trump’s hush-money-paying crony; and Najib Razak, the former Malaysian prime minister accused of massive corruption — to his cozy personal relationships with other powerful and problematic men (Charlie Rose, Steve Wynn, Bill Clinton). In elite legal circles, some speculate that Boies lived beyond question for so long that he lost his moral bearings. “I’m disappointed by how far he seems to have moved toward the dark side,” says Laurence Tribe, the liberal Harvard Law professor who was Boies’s co-counsel on Bush v. Gore. Then again, maybe the great David Boies was comfortable on the dark side all along.

“Everyone is entitled to a lawyer,” Boies likes to say. “But not everyone is entitled to me.” He was renowned for his superhuman abilities in the courtroom, which were matched by his strategic canniness when it came to shaping the public narrative. Boies cultivated reporters with charm and information and knew how to use his media connections to advance his case. “David has said on occasion that trials are essentially morality plays,” says Fred Norton, a former partner at his firm Boies Schiller Flexner. “Who the jury believes did the right thing, and being able to cast what you did in moral terms — that’s essential.”

In 2004, Weinstein’s imprint published Boies’s memoir, Courting Justice, a 490-page tome that for years was issued to every new associate at Boies Schiller. In it, he dispenses bits of his aggressive courtroom philosophy and retells the foundational story of his firm, which he decided to start during a visit to a Las Vegas casino. His game is craps, he writes, because it offers the best odds of beating the house. Boies likes to advertise this willingness to gamble, and his own career has tumbled along like a long lucky run.

Growing up in Orange County, Boies struggled with a reading disability, played cards for pocket money, and eloped as a teenager, eventually making his way to Northwestern Law School. His legal career was nearly derailed when he had an affair with a fellow student who also happened to be married to one of his professors. Boies turned the potential scandal to his advantage, persuading the dean to engineer his transfer to Yale. (He also married the classmate.) In 1966, Boies joined Cravath, Swaine & Moore, where he spent the next three decades, save for a brief tour in Washington, where he worked for Senator Edward Kennedy. There, he met the young lawyer who became wife No. 3, Mary McInnis Boies, to whom he has been married for 36 years.

Boies practiced high-stakes litigation, specializing in “bet the company” cases. At Cravath, he represented Texaco in an existential struggle with another oil company and tangled with Michael Milken and Carl Icahn, who later became a poker buddy and a client. The press celebrated him as a shambling genius with a savantlike memory and a wardrobe full of cheap suits from Sears. In fact, as Karen Donovan writes in her insightful biography, v. Goliath, Boies only started dressing like an Everyman after discovering it helped him with juries.

Boies’s stardom grated on some of his partners at Cravath. In 1997, he quit the firm, officially citing his desire to continue representing Steinbrenner and the Yankees, who had a conflict with another Cravath client.

“It’s like it’s 1956 and Mickey Mantle is suddenly a free agent,” Steven Brill, the founder of The American Lawyer, and a Boies pal, told the Times. Boies decided to start his own firm, based near his home in the Westchester suburb of Armonk. He was joined by Jonathan Schiller, a Washington attorney he had met while representing the energy conglomerate Westinghouse in a case that involved bribes it allegedly paid to the Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Later a third partner, antitrust specialist Donald Flexner, came onboard.

Boies intended for the firm to be an elite boutique, and although it quickly outgrew its founder’s expectations — it now has 15 offices with some 300 attorneys — it retained his swashbuckling attitude. For years, the New York office’s holiday party was held at a secretive Italian gun club in Greenwich Village, where its lawyers could test their aim in a basement shooting range.

Most high-priced litigation firms tend to specialize in defense, representing banks and institutions, because that’s where the reliable money is, but Boies was happiest on the offensive. He took some plaintiff work on contingency, where payoffs for victory could be enormous, and the firm offered an unusual compensation system that linked bonuses to the revenue lawyers brought in.

Boies is renowned for the deft, polite manner with which he leads opposing witnesses into his traps. His deposition of Bill Gates in a famous 1998 antitrust case against Microsoft is remembered as a masterpiece of clinical interrogation. His conversational cross-examinations are built on meticulous research, gathered and arranged by teams of associates.

He knows how to leverage damaging information. One partner at his firm told me of being with Boies at a trial in which the judge seemed particularly hostile to their client. In response to a series of leading questions from opposing counsel, Boies objected: “But your honor,” he said, “that’s like asking, ‘When did you stop beating your wife?’ ” The judge acted aghast, and the partner later learned why — he had once been accused of domestic violence. She assumed Boies had committed a gaffe. But other lawyers at the firm assured her otherwise. “He was trying to send a signal to the judge: I’ve got your number,” the partner told me. “I actually can’t think of another attorney who balances such total confidence, self-possession, and calm with an ability to take a knife and stick it in someone in a pointed, specific, and targeted way.”

Boies could also respond with blunt force, particularly if his own interests were at stake. In 2002, two former Boies Schiller associates brought a sex-discrimination case against the firm. They challenged its practice of dividing associates into two tiers, one that was tracked toward partnership and another with lower pay and (supposedly) more flexible hours. The plaintiffs claimed that all of the male associates in the Armonk office were on the partnership track, while the lower tier was made up entirely of women. Their attorney, Hillary Richard, called the non-partnership track a “female ghetto.”

Boies denied the allegations ferociously. “It was the most scorched-earth matter I’ve ever seen,” Richard says. “You knew he was going to get mad and fight hard. I don’t think they knew how mad and how hard.” Boies conducted the deposition of one plaintiff himself, attacking her honesty and work ethic. The women settled the suit, accepting $37,500 each, a resolution the case’s judge termed “conspicuously lean.” An investigation by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found “reasonable cause to believe” their claims. (The firm says it resolved the case without penalties or mandated changes.) The Wall Street Journal, in a cheeky headline, called the firm the “Old Boies Club.”

Boies Schiller was run like a family business. Around the firm, people would joke that the firm had a nepotism policy and it was pro-nepotism. Boies’s wife, Mary, worked there. So did his ex-wife, Judith. So did four of his six children at various times. One of Schiller’s sons is also a partner. One of Boies’s closest confidantes is the firm’s chief financial officer, Amy Habie, whom he first met as a pro bono client. He represented her in a string of lawsuits over a dozen years involving her divorce, an international child-custody dispute, and her Palm Beach landscaping company, in which Boies also had an investment stake. At some point, Habie joined Boies Schiller. For a time, she managed the firm’s financial affairs from a portable office at her plant nursery.

“Would we have preferred some former Ernst & Young person to be the CFO versus Amy?” a former partner asks rhetorically. “It was just one of those idiosyncrasies that was strange about the firm.” The firm’s quirks were easy to tolerate, though, because everyone who worked there was getting so incredibly rich — and Boies, as the firm’s founder, was getting richest of all. “He didn’t really build a law firm,” says a longtime friend. “He built a money machine tied to David Boies.” Over the years, he came to live like the clients he represented, acquiring a world-class racing yacht and a couple of California vineyards. He sometimes shot craps with Nora Ephron on visits to Las Vegas. She and Boies were in the room, along with his friend Barbara Walters, on the infamous evening in 2006 when casino billionaire Steve Wynn, a Boies client, accidentally poked a hole in his Picasso.

Boies was also tight with Charlie Rose, with whom he shared a Paris pied-à-terre (along with Mort Zuckerman). When the magazine Radar, in 2007, wrote about Rose’s alleged groping behavior as part of a cover story on “toxic bachelors,” Boies demanded a retraction on his friend’s behalf. (He didn’t get one.)

Boies might put on morality plays in the courtroom, but he was less judgmental when it came to choosing his clients. His firm prides itself on taking tough cases, which means it often finds itself defending people who are accused of reprehensible actions. “It’s kind of literally what we do,” says Phil Korologos, a partner at the firm who has worked closely with Boies for decades. Boies Schiller defended an executive of the mercenary firm Blackwater in a federal arms-trafficking case, in which the government ultimately dropped the charges. (Blackwater founder Erik Prince is a friend of Boies’s.) Boies unsuccessfully defended Philip Morris against lawsuits by ex-smokers, even after one of his daughters died of lung cancer.

Boies didn’t want to be remembered, though, as just another lawyer-for-hire. In 2009, he took on a case that he hoped would serve as a righteous capstone to his legal career. At the invitation of attorney Theodore Olson, his opponent in the Supreme Court argument of Bush v. Gore and a conservative convert to the cause of marriage equality, he agreed to represent a group of plaintiffs seeking to overturn Proposition 8, the California law banning gay marriage. Their suit caused great division within the marriage-equality movement, with many strategists warning that pressing the case was recklessly premature. Boies argued that the country was changing. “He’s not stupid; he doesn’t take bad risks,” says Olson. “But when he’s developed a confidence in his own mind about what he’s about to do, he’s willing to take a chance.”

In March 2013, the case reached the Supreme Court. Olson handled the oral arguments, but afterward, addressing the media outside, Boies took the lead, throwing an arm around his former adversary. “Those of you who were in court today,” Boies said, “saw why I like it a lot better when this guy is on my side.”

Boies has a preternatural ability to divide his concentration among many seemingly all-consuming problems at once. That morning on the steps of the Supreme Court, some incalculable proportion of his attention was focused on the other side of the continent. The day of the argument, a movie producer named Scott Steindorff had called him from New Mexico. In 2012, Boies had decided to dabble in the glamorous — and highly speculative — movie business, forming the Boies/Schiller Film Group with Zack Schiller, one of Jonathan’s sons. They had made a major investment in a highbrow Oscar vehicle called Jane Got a Gun — a feminist Western starring Natalie Portman. It was something of a family project. Boies’s daughter, the actress Mary Regency Boies, was a producer.

Steindorff was calling Boies to tell him the movie was facing disaster. “He was on the steps of the Supreme Court,” Steindorff later told The Hollywood Reporter. “He said, ‘Can this wait?’ I told him no.” The week before, the movie’s original director, Lynne Ramsay, had quit the project just as principal photography was scheduled to begin. The producers would later file a lawsuit, claiming she had blown a deadline for a script rewrite and been “generally disruptive,” showing up to the set intoxicated and waving a prop gun. (Ramsay called the allegations “simply false,” and the suit was settled.) Now Steindorff told Boies he desperately needed more cash to keep the movie alive.

Boies anted up. According to records filed in court, over the spring of 2013, his film company made an escalating series of investments in Jane Got a Gun, amounting to more than $20 million, most of which came from him and Schiller personally. Yet the film was beset by an epic series of mishaps. The actor cast as the villain, Jude Law, was replaced by Bradley Cooper, who was replaced in turn by Ewan McGregor. The Hollywood press took dead-eyed aim. (Sample headline: FILMING JANE GOT A GUN IS BECOMING A CALAMITY.) Boies visited the set, where his daughter was trying to manage the crisis.

In order to reach an audience, Jane Got a Gun needed a distributor. That May, at the Cannes Film Festival, Weinstein announced a deal in partnership with Relativity Media to distribute and market the film. The movie appeared to have been saved, and The Hollywood Reporter hailed Boies as the saga’s “unlikely hero.” In a happy plot twist, his daughter ended up marrying Noah Emmerich, one of the lead actors.

In June 2013, the Supreme Court effectively invalidated Proposition 8, while declaring the federal Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional in a separate decision, setting the stage for its landmark ruling in favor of marriage equality two years later. Boies’s daring bet would be chronicled in books and a critically acclaimed documentary. Meanwhile, his client relationship with Weinstein had taken on a more complicated dimension. They were now in the movie business together.

For many years, Boies had played a key informal role in Harvey Weinstein’s company. “David was his closest adviser,” says the entertainment attorney Bert Fields, who also represented the Weinstein Company. “I think he was a restraining influence on Harvey.” Boies was often called on to moderate disputes between the Weinstein brothers. Harvey was the Oscar-winning impresario, but Bob’s side of the business, which specialized in horror and science-fiction movies, was more commercially successful. Their tensions constantly erupted into fraternal feuds. When Harvey was raging, Boies would try to lead him back to reason. “David was one of the few people that Harvey had a tremendous amount of respect for,” says David Stone, a former Boies Schiller partner, who now heads the firm Stone & Magnanini.

It wasn’t just the advice that Weinstein valued, it seemed, but the ego gratification that came from knowing that his superlawyer was looking out for him. “There was something that so delighted him when he would talk about David Boies,” says a media executive who once worked for Weinstein. “Harvey didn’t need legitimacy in Hollywood, but he was always a little outré in New York circles of a certain kind. And I think Boies had that intellectual, social veneer that Harvey saw and thought was maybe transferable.”

Several of Weinstein’s other attorneys have told me they were surprised by the sheer breadth of Boies’s attention to Weinstein. “David was a fierce advocate for Harvey and acted to protect his reputation,” says one. “For Harvey, David would always get on the phone.” When I asked him to describe the role Boies played in the constellation of lawyers Weinstein employed, he asked me to put down my pen, paused dramatically, and said: “Consigliere.”

What Boies got out of the relationship is less immediately obvious. The Weinstein Company had a big name in Hollywood, but it wasn’t a huge source of revenue for Boies Schiller in comparison to clients like Goldman Sachs or DuPont. Some who know Boies suggest his paternal loyalties may have played a role. The Weinstein Company was represented day-to-day by his son Christopher, who headed Boies Schiller’s since-disbanded corporate-law group. And Weinstein could aid his daughter’s movie career. A source close to Boies offered another explanation, saying Weinstein was a needy client who preyed on one of Boies’s few weaknesses. “David likes to swoop in and help people,” says the source. “And Harvey manipulated that.”

What exactly Boies knew about Weinstein’s conduct toward women is a matter of contention. But no one at Boies Schiller possessed any illusions about their client’s character. “I couldn’t imagine that anyone who was ever in the presence of that guy for five seconds didn’t know he was a thug,” says a former partner. Another former lawyer at the firm told me she was warned by friends in the entertainment industry that she should never allow herself to be alone with Weinstein.

By 2015, the rumors about Weinstein were becoming impossible to contain.

That March, an Italian model named Ambra Battilana went to the police, claiming that Weinstein had grabbed her breast in an encounter at his office. Battilana had taped subsequent conversations in which the producer made what sounded like incriminating admissions. The allegation came at a particularly fraught moment for Weinstein. His company was going through financial stress and a creative drought, and his contract was up for renegotiation. Weinstein suspected his investors wanted to use the sexual-assault allegation as a pretext to wrest control of the company. He assembled a team to deal with the crisis, calling on Rudy Giuliani’s law firm, a top criminal-defense attorney, and, as always, Boies.

Ken Auletta, the New Yorker writer, pursued a story about the allegation. A decade earlier, Auletta had discovered that Weinstein had paid legal settlements to at least two women in connection with an alleged assault incident at the Venice Film Festival. Weinstein claimed the incidents had been consensual, and Auletta was unable to convince the accusers to be identified. Auletta suspected Weinstein might have used corporate funds to guarantee the women’s silence, but at a meeting with Boies and Weinstein, Auletta was shown canceled personal checks. In 2015, when Auletta called Weinstein about the new allegation, the producer quickly arranged for the journalist to meet Boies at his Manhattan office, along with his criminal attorney and a private investigator. They presented a folder of documents meant to undermine Battilana’s credibility.

Weinstein’s legal team reportedly retained private investigators in Italy to dig up dirt. News articles soon appeared in tabloids in which anonymous sources “close to Weinstein” portrayed Battilana as a blackmailer with “a history of pursuing older men.” (Boies later claimed to have evidence she had once worked as a prostitute, an allegation she denied.) The decision about whether to charge Weinstein fell to Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance Jr., for whom Boies had been a campaign fund-raiser. (Vance’s office says it had no interactions with Boies on this matter.) Vance dropped the investigation, reportedly because of concerns about Battilana’s reliability as a witness. Weinstein’s attorneys reached a confidential settlement with Battilana, which required her to sign a sworn affidavit disavowing her accusation. Auletta decided not to pursue his story further. He had gotten to know Boies well over the years as a journalist and considered him “a social friend.” Months later, Auletta asked him how he could continue to represent a man like Weinstein. Boies told Auletta he was loyal.

Even after the DA dropped the investigation, Lance Maerov, Weinstein’s loudest critic on the company board, demanded to review Weinstein’s personnel file to determine if there were other incidents of misconduct. Weinstein enlisted Boies to fend off the request. Boies urged Harvey and Bob to set aside their differences and face down their common enemies on the board, advising them in one email to “prepare a war plan as well as a peace plan.”

In early August 2015, after Maerov complained that Weinstein had threatened to beat him up at a movie premiere, Boies drew up a scathing letter. “If you believe that Harvey was really threatening or intending to attack you physically, that is as good an indication of your paranoia concerning Harvey as I can think of,” Boies wrote. He claimed that information given to Maerov had been “repeatedly leaked” and that he could not be trusted with the personnel file because of his “obvious personal animus.”

In a group email, however, Bob Weinstein cautioned Boies that there were witnesses who backed up Maerov’s account. “Might not be as absurd as u would like to believe,” Bob wrote, and then addressed his brother, who was cc’d on the email. “Harvey, the anger is a problem, the worse problem is not dealing with it.”

Around the same time, Boies attempted to smooth over a concern that Harvey might quit over the contract dispute. “Harvey wants to stay,” Boies wrote to Bob in a long, plaintive email. “He knows this is his highest and best use and that anywhere else he would not have either the freedom or the economics he can have here.”

Bob responded by referring back to a “personal situation” that he said he had discussed with Boies and his brother before. “The other thing of concern, is that while Harvey has responded to a hundred emails concerning many business topics, the one email that he has failed to respond to is the one that commits him to treatment,” Bob wrote, adding that “there must be consequences if he doesn’t commit, otherwise it is worthless.” In a statement, he says he knew nothing of allegations of “significant sexual misconduct” until the rest of the world found out in 2017. At the time, Bob said, “he had come to the conclusion that his brother had issues regarding fidelity to his marriage and that he may have been suffering from some form of sex addiction.” Two women who worked for the Weinstein Company subsequently told the Times they escorted him to sex-addiction therapy in 2015.

Boies was able to prevent Maerov from gaining access to whatever documentation was in Weinstein’s personnel file. Instead, it was given to yet another prominent attorney, H. Rodgin Cohen, of Sullivan & Cromwell, for an independent review. (Cohen’s objectivity is disputed; Maerov later learned his son worked for the Weinstein Company.) Cohen assured the board that there were “no unresolved claims.” Weinstein was given a new contract. In contrast to the old one, which allowed the board to fire him only in extreme circumstances, such as a felony conviction, the new contract contained a code of conduct. Violations of the code could result in financial penalties or even Weinstein’s termination, provided a board majority — including his brother — voted for it.

In November 2015, after the new contract was signed but before it took effect, Bob informed board members that there was a new complaint against his brother, contained in a memo written by a 28-year-old production executive named Lauren O’Connor. It outlined allegations of a “toxic environment for women,” relating incidents that included descriptions of the producer’s sexual advances toward young female employees. Maerov was alarmed. But Boies promptly helped to negotiate a confidential settlement with O’Connor. He assured the board that the matter had been resolved amicably and the complaint withdrawn.

Maerov would later complain that Boies “obstructed” his efforts to figure out what Weinstein was up to. He and another board dissident, film producer Tarak Ben Ammar, focused particular criticism on what they described as an apparent conflict of interest. Unbeknownst to them, they claimed, at the same time Boies was representing Weinstein in his fight with the board, he was negotiating a personal business deal with the Weinstein Company.

That same summer of 2015, Jane Got a Gun once again needed a rescue.

Relativity Media, the Weinstein Company’s partner in the film’s distribution deal, was collapsing financially, and it was possible the release would be frozen by bankruptcy proceedings. Boies managed to snatch back control, in a deal sealed in late July, during the most heated period of wrangling over Weinstein’s personnel file. That September, the Weinstein Company announced a new agreement to distribute Jane Got a Gun.

The movie opened in more than 1,200 theaters in early 2016, a fairly wide release for an art-house film. But Weinstein gave the film meager promotion, and it grossed just $1.5 million domestically, according to the website Box Office Mojo, making it one of the poorest-performing films the Weinstein Company ever released. “Weinstein clearly ended up hurting all of us, including David,” says the producer, Steindorff. “He did not fulfill his obligations.”

Boies didn’t appear to hold a grudge against his client, though. He later invested $10 million in the production of two other Weinstein Company films.

In March 2016, Boies’s wife threw him a lavish 75th-birthday party in Las Vegas. A few hundred of his dearest friends and clients convened at Steve Wynn’s resort for a weekend of steak and gambling. Ted Olson was there. So were Erik Prince, Tom Brokaw, and Ray Kelly. One guest has a distinct memory of running into Weinstein during the Friday-night kickoff party, held at a nightclub called Surrender.

“It was kind of a love-in,” recalls Joel Klein, who as a Justice Department official hired Boies for the Microsoft case and later became New York City schools chancellor. The guests were all given a thick binder containing a collection of first-person testimonials titled The Book on David Boies, which included reminiscences from family members, clients, and media luminaries. Longtime friends offered up toasts. The most memorable speech was delivered by an embattled client, the young biotech entrepreneur Elizabeth Holmes.

Over the previous five years, Boies had helped to guide Holmes’s start-up, Theranos, through a remarkable rise and crash. The secretive private company claimed it had developed a revolutionary blood-testing technique. Boies Schiller had accepted around 320,000 shares, valued at the time at $4.8 million, as payment for a portion of its legal fees, which were later individually distributed among several partners, including Boies. He stood to profit immensely if Theranos succeeded as promised, and for a while it did, as a speculative fever inflated its value to $9 billion.

Then a reporter from The Wall Street Journal, John Carreyrou, began questioning the hype. Boies fought hard to kill the investigation, pressuring the Journal and threatening lawsuits against former Theranos employees suspected of talking to the paper. The Journal published its article anyway, suggesting that Holmes had been misrepresenting Theranos’s technology.

Afterward, according to a source close to Theranos, Boies and attorneys from his firm drafted a defamation complaint against Carreyrou and his news organization, and pushed to file it, although the company ultimately declined to do so. The source said that whenever questions arose from the press or regulators, Boies would steer the company in a confrontational direction: “In retrospect, that was shortsighted strategy driven by misapprehension of the stakes and the facts, and at the heart of that strategic decision was David Boies.”

At the party, Holmes made a display of her devotion. “If it wasn’t for people like David, people like me would never have a chance,” one person who was there recalls her saying. The tribute from a possible fraudster was uncomfortable for many of Boies’s friends. “The older people in the audience were stunned that that was the person he had chosen to stand up for the toast — the David Boies of old would never have done a thing like that,” says someone who has long known him. “Somewhere along the line, he made a U-turn.” The next month, news broke that Holmes was under federal investigation.

Boies often describes his loyalty as one of his bedrock virtues and says he sticks with his clients so long as he feels like they’re taking his advice.

But the principle appears to have its limits. After a falling out over how to deal with the investigation, his firm parted ways with Theranos later in 2016. Boies began to suggest he was duped by Holmes, complimenting Carreyrou’s reporting and claiming he would never threaten to sue a news organization. Holmes was indicted on federal fraud charges this past June.

Attorneys are obliged to represent their clients in good times and bad, but the ethics get tricky when a lawyer’s advocacy protects a client who nevertheless continues perpetrating crimes. Boies has said that, in retrospect, he “knew enough” about Weinstein’s alleged misconduct in 2015 to have taken some action. Even many admirers struggle to explain why he didn’t end his representation then. After all, notes Deborah Rhode, the Stanford ethicist, he was a civil litigator, not a public defender representing an indigent client. “The kind of behavior reflected here is what you see sometimes in people who get into positions of power and lose any sense of accountability,” Rhode says, arguing that Boies suffered from “moral myopia.”

In 2016, a new crisis arose for Weinstein, which drew Boies in even deeper. This one had nothing to do with sex — at least initially. A faction of board members of the AIDS charity amfAR, who were critical of the organization’s chairman, the footwear businessman Kenneth Cole, raised questions about a financial arrangement the nonprofit had made in connection with an annual Cannes auction gala. Weinstein, a major amfAR fund-raiser, had insisted that $600,000 in proceeds raised from items he had donated be redirected to another nonprofit, the American Repertory Theater. That March, at the instigation of Cole’s critics on the board, the charity hired attorney Tom Ajamie to conduct an investigation.

Weinstein stonewalled Ajamie, who submitted a report concluding that the shuffling of charitable funds was at least suspicious and possibly illegal.

(Later, after the Times reported that the donation may have defrayed Weinstein’s investment in the theater’s production of his musical Finding Neverland, the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan launched its own investigation, which appears to be ongoing.)

In the course of looking into Weinstein’s charitable activities, Ajamie began to hear other stories. “The first thing people say is ‘He’s a bully, he rapes women, he’s a predator,’ ” Ajamie recalls. (Weinstein has always denied abusing anyone.) In mid-October 2016, after Ajamie’s report was submitted, word made its way back to Weinstein that the lawyer had been asking questions about his sexual conduct. While Boies and Charlie Prince, a Weinstein Company attorney, repeatedly tried to contact Ajamie regarding what Boies later described as his “false and defamatory statements,” Ajamie met with a well-known advocate for sexual-harassment victims, the L.A. attorney Lisa Bloom. He suggested she might be interested in representing Weinstein’s accusers in a potential lawsuit. (She didn’t take him up on it.) Around the same time, on October 14, 2016, actress Rose McGowan posted a series of tweets that seemed to be directed at Weinstein, claiming: “it’s been an open secret in Hollywood/Media & they shamed me while adulating my rapist.”

Weinstein was enraged. He called Cole and told him that if amfAR was going to pry into his sexual affairs, he would investigate Cole and his board members’ own personal lives. He wasn’t bluffing. On October 24, Weinstein retained private investigators. Such firms, often staffed by former FBI and CIA agents, are frequently contracted in connection with corporate crises.

Weinstein had heard about one called Black Cube, which advertised itself as “a select group of veterans from the Israeli elite intelligence units” and promised a more “creative” approach than the competition. (“We always heard they were, like, bad guys,” says one person who works for a firm that uses private investigators.) On its website in 2016, Black Cube boasted of its success in thwarting a “high level criminal” investigation. Weinstein contacted former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak, a friend, who helped him get in touch with the firm.

Private investigators usually act as subcontractors of law firms, an arrangement that preserves a veneer of attorney-client privilege and supposedly provides for legal supervision. Boies Schiller’s corporate-law group, overseen by Chris Boies, negotiated a contract with Black Cube, and Amy Habie signed it on the firm’s behalf. (It was subsequently leaked and reprinted by the Daily Mail.) Under its terms, Black Cube would be paid $100,000 a month to conduct an operation using what the firm called its “Blitz methodology.” The objective, the contract stated, was to “identify the entities behind the negative campaign against” Weinstein. Black Cube’s initial target list reportedly included journalists, at least one potential Weinstein accuser (McGowan), and amfAR figures, including Cole and Ajamie, who says he started hearing about odd unannounced visitors showing up at his office and apartment building.

AmfAR bowed to pressure from Weinstein. “The board was mad,” Ajamie recalls. “Saying, ‘Oh my God, David Boies is calling.’ ” It commissioned a second attorney to investigate the auction transaction, who determined the charity had done nothing illegal or unprecedented. But Weinstein wanted to be sure Ajamie would stay quiet. That winter, Ajamie attended the Sundance Film Festival, where Bloom —acting as a friend, Ajamie believed at the time — arranged for a sit-down with Weinstein. Over breakfast in his hotel suite, Weinstein launched into what Ajamie describes as an “unhinged” harangue. He claimed he had slept with countless actresses, which he said was only natural given his position, but he denied he was a rapist. At the end of the meeting, Ajamie claims Weinstein badgered him to sign a nondisclosure agreement.

“You’ve got to do it,” Ajamie recalls him saying. “Boies wants you to sign it.”

Ajamie refused, and Boies fired off an email to amfAR’s attorney. “I learned at breakfast with Mr. Weinstein this morning,” he wrote, “that, contrary to amfAR’s assurances, Mr. Ajamie was continuing in December 2016 and January 2017 to investigate, threaten, and defame Mr. Weinstein.” AmfAR board members were presented with NDAs that prohibited them from assisting any further inquiry, along with a promise of a $1 million donation from Weinstein. Most signed. “I was thinking, Why in the world is Boies involved in this nonsense?” Ajamie says. “Why is Boies asking me to go silent about things I know that are really ugly, dirty, and maybe illegal?”

For a time, the maneuvering succeeded. A month after Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election, Weinstein and Boies were spotted at Rao’s, having a consoling dinner with Bill and Hillary Clinton. Reporters were continuing to circle, though, and Weinstein decided to erect further defenses. He retained Charles Harder, a libel lawyer best known for winning a publication-killing legal judgment against Gawker, and Washington attorney Lanny Davis, who specializes in crisis-management communications. Davis, who had collaborated with Boies on previous cases, told me that Weinstein originally brought him on to handle his problems with women, but he later shifted to dealing with the amfAR dispute after Megan Twohey, an investigative reporter at the Times, began to look into it.

“We were sitting in a room and Harvey was trying to explain this whole complicated transaction,” Davis recalls. “He said, ‘I’ll tell you who can explain it to you.’ Then he dials a number and I hear a familiar voice, and it’s David.”

In the fall of 2016, a colleague at this magazine, Benjamin Wallace, was trying to report a story about Weinstein’s rumored abuses and had been contacting some of his alleged victims. (None of the women was ready to come forward, and the investigative project was eventually shelved.) Wallace told me he’d been contacted by a woman with an unplaceable accent who identified herself only as “Anna.” She claimed she had a story to tell as a former Weinstein mistress. But she was cagey about details and seemed most interested in knowing what other women were prepared to say. Something about Anna’s affect seemed off. Wallace confided to me at the time, “I think she’s a spy.”

As it turned out, she was. “Anna” was actually a former Israeli military officer and actress named Stella Penn Pechanac, and she was working for Black Cube, trying to figure out what reporters had on Weinstein. Impersonating a feminist philanthropist, Pechanac also befriended McGowan and got her to convey the contents of a memoir she was writing. McGowan told Pechanac that she had talked to Ronan Farrow, who was then working on a Weinstein investigation for NBC News. Farrow was reportedly contacted by Black Cube and also by Bloom, allegedly, who warned him to be wary of his source. At some point, Weinstein had brought Bloom into his fold. In March 2017, she announced that Weinstein and Jay-Z were developing a TV series based on a book she’d written about the Trayvon Martin case. (Bloom wouldn’t comment for this story.)

Weinstein and his legal team put intense pressure on NBC. According to a recent internal investigation conducted by the network, Weinstein and Boies had repeated contacts with top executives. Lanny Davis showed up, unannounced, at the network’s Rockefeller Center headquarters to tell the boss of the news division that McGowan was not credible, and Bloom and Harder had similar interactions. Farrow’s story never aired, and he was despondent. “I had moved out of my home because I was being followed and threatened,” Farrow said in a speech last spring at Loyola Marymount University. “I was facing personal legal threats from a powerful and wealthy man who said he would use the best lawyers in the country to wipe me out and destroy my future.”

Farrow was also facing competitive pressure from the Times, which was continuing to gain momentum in its reporting on Weinstein’s behavior. It had obtained a crucial piece of hard evidence: Lauren O’Connor’s memo. On October 5, the Times published a front-page story by Twohey and Jodi Kantor describing O’Connor’s complaint and relating allegations of a handful of named and unnamed women, including actress Ashley Judd. Weinstein released a bizarre statement, blaming the “culture” he had grown up in, quoting Jay-Z, crediting Bloom for being his “tutor,” and vowing to “conquer my demons.”

In emergency meetings with his board, Weinstein was venting particular anger toward his brother, who he believed had leaked the document to the Times. (Two sources told me the O’Connor memo was more likely leaked by someone else within the company.) Four board members swiftly resigned. On Sunday, October 8, Bob Weinstein and the remainder of the board voted to fire his brother. Two days later, The New Yorker published the first in a series of articles by Farrow, reporting allegations from 13 women against Weinstein ranging from harassment to rape.

Through this final drama, Boies was uncharacteristically reserved; at long last, he seemed to have lost his influence over Weinstein. He was also somewhat distracted, as he was dividing his attention among multiple disasters. The Sunday evening of the board vote, out in Napa County, a wildfire tore down the slope of Atlas Peak, where Boies co-owns a 20-acre ranch. It quickly incinerated everything on the property, including a vineyard where Boies grew grapes for his wine Aequitas, named after a Latin term for “justice.” By the time the flames were extinguished, all that was left of the Aequitas estate was a single black bottle, twisted by the heat.

One day this summer, I had lunch with David Boies at one of his favorite haunts, Sparks Steak House. In the eight months since the Weinstein disclosures, which catalyzed the #MeToo movement, sexual-misconduct allegations had swept up many men in Boies’s world, including his friends Wynn and Rose. Publicly and privately, Boies had expressed concern over the furiously judgmental climate for accused offenders and their lawyers alike, drawing comparisons to the McCarthy era. Over the course of nearly two hours, I asked Boies a number of questions about uncomfortable subjects, including a federal criminal investigation of Black Cube, the existence of which had not yet been reported publicly. Boies explained that he was constrained in what he could say by attorney-client privilege and the demands of Weinstein’s current lawyers. But he offered some surprisingly candid answers, if only off the record.

Maybe something about the conversation got him thinking. A few weeks later, he invited the veteran Times business columnist James Stewart, a former colleague from Cravath with whom he had long been discussing an interview, up to his mansion in Westchester. They had a soul-searching on-the-record chat over a glass of French wine. In the resulting profile, Boies portrayed the tactics he employed as ethically acceptable — even principled. “A lawyer does not have the choice of how to represent a client,” he told Stewart. “If we decide any class of accused is not deserving of aggressive representation simply because of what they’re accused of, then we undermine the protections that are essential for all of us.”

Using the rhetoric of civil liberties to justify a spy operation to smother rape accusations was a gymnastic argumentative maneuver. And countless friends, collaborators, and current and former employees of Boies tell me they still can’t believe the man they knew — an avowed friend of the press — would ever knowingly sanction such a thing. But the outlines of Black Cube’s work for Boies, first reported by Farrow in November 2017, left little room for feigned ignorance. The New Yorker reprinted a copy of a second contract between Boies Schiller and Black Cube, signed in July 2017, that described the operation in minute detail, referencing the pseudonymous agent “Anna” and a second agent posing as an investigative journalist who was to “promptly report” back the results of his interviews, and offering a $300,000 bonus for foiling the publication of a “negative article.” The document was signed by David Boies.

The Times, which was paying Boies Schiller to represent it in a libel case, issued a statement calling the operation “reprehensible” and fired the law firm. District Attorney Vance, who was pursuing new rape charges against Weinstein, and the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan, which was probing the amfAR transaction, both broadened their investigations to look into possible crimes, like wire fraud, committed during the Black Cube operation. Meanwhile, New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman sued the Weinstein Company, claiming its leadership had “repeatedly and persistently violated the law” in covering up alleged abuses via confidential settlements and other means. (Schneiderman would soon resign after Farrow and Jane Mayer reported on his own allegedly abusive history.) The Weinstein Company filed for bankruptcy. Boies and his firm are among its largest creditors, owed $4.5 million for legal fees and another $8.8 million in film proceeds.

Some corporate litigators shrug off the Black Cube revelations, saying the only thing that was surprising was that all the embarrassing details escaped the usual vault of attorney-client confidentiality. “That happens, it doesn’t shock me,” Bert Fields says of the firm’s impersonation practices. “I am 100 percent sure that David believed it was proper or David would not have done it.”

“The technique is a tool,” says another attorney who has dealt with Boies in the past. “Lizzie Borden misused the ax.” In recent months, Boies’s admirers have repeated this argument to me like a mantra: This is just what lawyers do. “David is a zealous litigator,” says his friend Joel Klein. “I understand that the world of litigation looks different to the media than it does to litigators.”

To those outside this professional circle, though, the Black Cube operation was appalling. In response, Boies issued a carefully worded email to his firm. He wrote that Weinstein’s “request to contract with investigators seemed at the time, like a reasonable accommodation for a longtime client,” but acknowledged it was “not thought through” and conceded that it “was a mistake to contract with, and pay on behalf of a client, investigators who we did not select and did not control.” He tried to rationalize away the conflict-of-interest issue by saying he thought he was actually serving the interests of the Times by testing the reliability of its sources. But beyond that, Boies sought to assign most responsibility to Weinstein and “his other counsel,” who he said were more closely involved in overseeing Black Cube. “Had I known at the time that this contract would have been used for the services that I now understand it was used for, I would never have signed it,” he wrote. “I would never knowingly participate in an effort to intimidate or silence women or anyone else … That is not who I am.”

Within Boies Schiller, there was great unrest, particularly among a group of younger associates, who saw his explanations as inadequate. Many of them had never seen a document like the Black Cube contract, which was stunning in its explicitness. And even if it were not — what did Boies think Weinstein needed ex-military intelligence operatives for, if not intimidation? It didn’t make sense. The Boies they thought they worked for was a courtroom crusader, not some backroom fixer.

In crisis meetings and back-channel chats, lawyers opened a discussion of the firm’s own culture and power structure. Some expressed qualms they had with other clients, like Oleg Deripaska. Some were outraged by the firm’s conduct in other cases, like an ongoing lawsuit that accused the novelist Emma Cline of plagiarism and cyberstalking. (The firm, which represented Cline’s ex-boyfriend and two women, had been accused of bringing up irrelevant details about Cline’s sex life as leverage in settlement negotiations.) The conversations revealed a more basic philosophical split about what it meant to be an ethical lawyer. The divide seemed more correlated to age than gender.

“They were just young and inexperienced, and they’ve not been in these situations,” says one female Boies Schiller partner of the lawyers who’d raised concerns. “It’s just very black-and-white to that generation.”

It was up to Boies to bridge the gap. Last December, at Boies Schiller’s annual firm retreat held at the Ritz-Carlton in Key Biscayne, Boies addressed the case in a question-and-answer session. The atmosphere was raw. Some lawyers cried. Boies was notably unapologetic about what he had done for Weinstein. If anything, one person close to Boies says, he “narrowed his contrition,” placing the decision in the context of a long-term client relationship.

“For some people, David was legal hero, and to see what happened was disorienting to them,” says Boies Schiller partner Damien Marshall. “He was answering every question, standing up and taking it. That made people feel that he was who they thought he was.” Some internal critics were less satisfied. One young associate, a former Hillary Clinton campaign worker named Ally Coll Steele, asked whether Boies might consider stepping down from his position. Boies dismissed the suggestion. The next month, in a Washington Post column, Steele announced she was leaving the firm to start the Purple Campaign, an advocacy group devoted to issues of sexual harassment.

There has been no mass exodus, though, and the firm’s clients do not seem repelled by the scandal. If anything, it might serve as an advertisement to a certain kind of client. “His brand,” says a Boies Schiller attorney, “is as someone who is called when you need a lawyer who is going to do anything to vindicate your interests.” Boies is still working incessantly, still involved in big cases, like a pro bono lawsuit that accuses the website Backpage of sex trafficking and another arguing for the reform of the Electoral College. The firm is defending the social club the Wing, in a case claiming its all-women membership policy is discriminatory. Boies Schiller remains unafraid to take on controversial clients. Over this year, it has taken up cases for Elliott Broidy, the former Trump fund-raiser, in a lawsuit that claims Qatari-sponsored computer hackers revealed his hush-money arrangement with a former Playboy Playmate, and Najib Razak, who’s being looked at by the U.S. Justice Department in relation to a $4.5 billion corruption scheme.

The Manhattan district attorney’s office arrested Weinstein in May. He now faces charges of rape and predatory sexual assault. Such cases are notoriously difficult to prove to juries, but even if Weinstein isn’t convicted of sexual assault, he might still face criminal charges for the cover-up.

Sources say both the DA and the U.S. Attorney’s office are scrutinizing Boies’s communications with Black Cube, obtained as a result of confidential decisions by judges. Boies contends that he “did not control” his subcontractor. Sources familiar with the correspondence say Boies and other Boies Schiller attorneys were frequently cc’d on emails and otherwise had involvement in coordinating the operation with Black Cube and Weinstein.

People who have been summoned to meet with the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan say that prosecutors have indicated keen interest in Boies’s oversight role. “We work responsibly for our clients and lawfully for our clients,” Jonathan Schiller told me in September, shortly after the Journal broke the news of the investigation. “And you can put this in your article: David’s integrity and honesty are beyond reproach.” (A Black Cube representative said their company also obeyed the law. “We do not believe in legal gray areas.”)

Nonetheless, the potential for federal charges against Weinstein set up the possibility for a depressing coda to Boies’s illustrious legal career. “We have always maintained that any work that Boies Schiller did for Harvey Weinstein in connection with Black Cube was completely legal and, under the circumstances, very reasonable,” Weinstein’s defense attorney Benjamin Brafman told me recently. But he pointedly referred to Boies as “a critical witness for Harvey Weinstein in connection with an ongoing federal investigation.” If Weinstein were to be charged, Brafman would be likely to argue that, in hiring Black Cube, his client was relying on the legal counsel of the best attorney in America, whose name is right there on the contract.

Charges against Boies himself seem unlikely. Prosecutors tend to shy away from charging attorneys with crimes stemming from their actions on behalf of a client. It is possible, though, that Boies could one day be put on the stand by Weinstein and his lawyers and forced to answer hard questions under oath. As Boies always says, trials are morality plays. He may finally have found a client who is truly entitled to his talents.

*A version of this article appears in the October 1, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!